- Edition: Henry V

Stage and Screen

- Introduction

- Texts of this edition

- Contextual materials

- Facsimiles

9The rise of spectacle: 1738-1872

In the early eighteenth century, a group of aristocratic ladies, the Shakespeare Ladies' Club, began to petition London's theaters to revive more Shakespeare plays in the original versions, with the result that John Rich produced nine performances of Henry V at the Theatre Royal in Covent Garden in 1738, the first return of Shakespeare's version to the stage in twelve decades, and it entered that theater's regular repertoire, though it remained much less popular than Shakespeare's tragedies (Smith 15). During this period, the play was pressed into the service of anti-French propaganda -- it saw yearly performances during the Seven Years' War with France (1756-63) -- and of royalist politics: to celebrate the coronation of George III in 1761, Henry Vwas performed twenty-three successive times, with the coronation scene from 2 Henry IVincluded as a nod both to the current king and to the growing popular taste for spectacular pageantry that was to reach its climax in the nineteenth century.

10Both this tendency toward pageantry and the use of Henry Vto respond to (and stoke) anti-French sentiment -- which had only increased with the onset of the French Revolution -- reached a high point with the impresario John Philip Kemble's performance in the title role in 1789, repeated fifteen times through 1792. "Kemble's version of the play," writes Emma Smith,

was clearly designed to clarify Henry's heroism within this context of contemporary popular anti-French opinion, and his adaptation . . . produce[d] a theatrical script which was to dominate the play in performance for the next half-century. It is striking how, apparently independently, Kemble's acting text closely resembles the first published version of Henry V, the Quarto text of 1600. (18)

The Chorus had long been cut in performance, since apologetic speeches for the inadequacy of theater seemed inappropriate for an increasingly spectacular and realistic theatrical practice. Without the Chorus, as the quarto text shows, a less ambivalent, more patriotic view of Henry and his war emerges, a view that Kemble's acting text underscored.

11Kemble's staging was elaborate, the stage packed in nearly every scene with supernumeraries, and though the popularity of the play waned after the Napoleonic wars, the emphasis on historical spectacle persisted into the nineteenth century. When William Macready revived Henry Vin 1839, he set a tone for painstakingly researched historical re-creations of costume, realistic pictorial representations, and an archaeological approach to the staging of Shakespeare. A long review in The Spectatorcomplained that the scenic effects in Macready's production "divert the attention too much from the poetry and the personation . . . the attempt physically to realize what can only be suggested to the mind, sometimes defeats itself" (qtd. in Smith 23). This, however, was a minority opinion; negative reviews tended to insist on more realism, on fuller spectacle than Macready -- even with his cast of seventy and his attempts to practice wearing his full plate armor at home -- had yet achieved. Macready's approach to Henry was adopted by Samuel Phelps for a revival in 1852, and more notably by Charles Kean for a revival at the Princess's Theatre in 1859 that was in many ways the apogee of the Victorian antiquarian approach to staging the play.

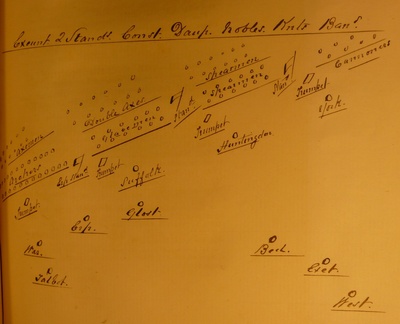

12Kean's production, staged in the years immediately following the Crimean War, may have stressed the antiquarianism so as to distance the play from the inevitable topical readings of critics and audiences. As Mrs. Kean's portrayal of the Chorus as the Muse of History suggested, historicism, or as Kean wrote, "Accuracy, not show," was the production's object, down to the playbill's printed descriptions of precisely reproduced costumes (Kean vii). Accuracy went hand in hand with lavish spectacle. The act one cast list included, in addition to named parts, twenty-nine supernumeraries. The onstage audience for Kean's "Once more unto the breach" speech (3.1) included, in addition to the king and thirteen lords, 7 Standard Bearers, 12 Glaive Men, 12 Spearmen, 12 Axemen, 12 Double Axemen, 24 Archers, 8 Commoners, 12 Lancemen, 12 Hatchetmen, 6 Harpoons, 12 French Spears, 4 French Knights, 4 King's Trumpets, 6 Body Guard, 10 French Boys, 20 English Boys," a total of 186 actors for a single thirteen-minute scene (compare the sketch below). Most famously, Kean replaced the Chorus's description of Henry's triumphal entry into London (5.0) with an actual parade through a recreated medieval city street, with real horses and more than a hundred actors, including two dozen dancers, eighteen aldermen, and the king's procession of knights, standard-bearers, archers, and cannoneers. The sequence drew much admiration, and occasional calls from the audience to reset and repeat it. Though it cut about 1,550 lines of the folio text, Kean's production ran more than four hours.

13Charles Calvert's production, opening in 1872 in Manchester and eventually touring in America, offers a counterpoint to the idea that Victorian staging necessarily sacrificed the play's inherent moral ambiguities on the altar of spectacle. Calvert was lavish in the Kean tradition -- his set for 5.2 recreated Troyes cathedral with Gothic arches and stained glass -- but relied on static, stylized tableaux for battle scenes that more effectively conveyed the violence than realistic representation could. His elaborate sets required a shortened version of the text, as Kean's had, but he retained many of the often elided moments in the play that trouble the heroic picture of Henry: the killing of the prisoners, the threats to Harfleur, and the hanging of Bardolph (Smith 31). And while the production repeated Kean's dumb show triumphal entry, in Calvert's hands it was "no indulgent, thoughtless escape into jingoism, but a judicious blend of rejoicing and sorrow" (Darbyshire 50). Calvert's version of the scene included an anxious knot of women waiting downstage for their returning husbands, sons, and brothers, one of whom collapsed with grief at the realization of her loss.